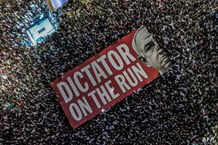

The victory of Boris Johnson and the Conservative Party in the 2019 UK election was another win in the column of avowed isolationist nationalists around the world before the COVID-19 pandemic engulfed the world. He rode to power on the promise of getting Brexit done: a movement to leave the EU driven primarily by its opposition to migration from Eastern Europe and perceived loss of sovereignty to a European Super-State. He can now safely ensconce himself among other world leaders such as Donald Trump, Recep Erdogan, Jair Bolsonaro, Viktor Orban, Andrzej Duda, Benjamin Netanyahu and our own Prime Minister, Mr. Narendra Modi, to name a few of the elected ones, not to mention authoritarian premiers in other countries like Xi Jinping, Vladimir Putin, and Mohammad bin Salman.

All these leaders have a few traits in common that make them nationalists. They talk about zero-sum games where if any other country wins, it must be at their expense. They revel in culture wars and make it seem that the majority is under siege. They detest liberalism in all forms. So, it seems obvious that they become natural allies on the world stage and usher in a new right-wing alliance that dominates the upcoming decades. Many would see this as the natural course correction to a post-Cold War liberal consensus that dominated the world economy and social thoughts till the global recession of 2008 and a few years thereafter.

But this begs the question if nationalists can form alliances? If they cannot stomach compromise, which they view as a loss, can they ally in common interest with any other country? So far, the answer seems to be a resounding “yes”. From White House Visits of Jair Bolsonaro to an assault on sense and sensibilities in the “Howdy Modi” and “Namaste Trump” extravaganza, to the buddy shake Putin and bin Salman greeted each other with at the G20 summit; at each of these, the leaders seemed to be tripping over to roll out the red carpet for their brethren-in-belief. But pull behind that curtain and certain fault-lines emerge clearly.

A particular exchange highlights this conundrum. Donald Trump has been an ardent defender of Benjamin Netanyahu. He also has found common ground with Andrzej Duda and gave his first speech in Europe in Warsaw. But Duda rubbed Netanyahu the wrong way when he signed a bill to absolve the “Polish Nation” of any role in the Holocaust. Can such leaders come together based on ideology?

Consider, furthermore, that Jared Kushner, an advisor to Donald Trump and his son-in-law, counts both Netanyahu and bin Salman’s personal allies. Maybe, an alliance between Saudi Arabia and Israel is the ultimate end-game in the “Middle East Peace Plan”. It remains an open, valid, and loaded question, though, whether the self-proclaimed defender of the Islamic Faith can reconcile with an Israeli leader who seems increasingly prone to abandon any notion of the possibility of a Palestinian State.

And coming to India and our Prime Minister Narendra Modi, the question can be asked whether he can align with Boris Johnson, who has often spoken gloriously of British Colonialism and has a history of racist statements, but are otherwise united against what they dub “anti-Hindu” sentiments? Recently, Johnson announced the reintroduction of the two-year post-study work route for Indian students in the UK that was scrapped by his own party at the beginning of this decade. If this was offered as a sop to Indians, it remains to be seen if that affects his standing amongst his base once implemented because he fought on reducing net migration into the UK. He has since unveiled a pledge to move towards point-based immigration which complicates projecting how the new student visa policy will work post this policy implementation.

Similarly, beyond the bear hugs, can Narendra Modi and Donald Trump have any semblance of a working alliance that is not rooted in shared grievances against liberals and elites? However close the two might be, it is doubtful our Prime Minister can ask Mr. Trump to admit more Indians into the USA, considering how personally antithetical to immigration the President of USA is. In fact, during the pandemic, Mr. Trump’s not-so-veiled threat to India to release Hydroxychloroquine or face repercussions and suspending all immigration, which affects a lot of Indians, already shows his real inclinations.

The above-highlighted instances of frictions, ideological divide, and political considerations at home highlight the paradox of nationalists forming an international alliance. If one considers their own nation above all else, then by definition, they have to consider the interest of other nations beneath them. Hence, any deal they make with another nation where they consider giving up something, that becomes something that their own voting populace can beat them with.

It is here that the opportunity for the Left becomes clear. The Left has been decimated in all these countries by these conservative nationalist leaders. Many of the influential think-tanks have proceeded to write obituaries of liberal thinking and roundly castigated leaders like Jeremy Corbyn in the UK, who had sought to make a case for economic socialism. But, in order to analyze properly if liberal economic thought remains viable, it is important to note why people like Mr. Corbyn lost in the first place.

The traditional heartlands of the left-wing Labour Party in the UK voted to leave the European Union in the Brexit referendum. Mr. Corbyn, a natural Eurosceptic, did not want to go against that vote but was forced to when certain Labour MPs, wishing to position themselves against a Tory Party hell-bent on delivering Brexit, quit the Labour ranks. The moment that happened, Mr. Corbyn had to promise another vote on Britain leaving the EU. The liberal heartlands saw it as a betrayal and abandoned the labor party in droves. It becomes clear that this was the turning point because just two years ago, in 2017, Labour with a similar economic manifesto, but no commitment on going against Brexit, had registered its biggest increase in vote share since 1945.

While Labour lost in its heartlands, it could not pick up seats in the south, in and around London, because these traditional Conservative Voters, though primarily voters of “Remain” in the referendum and socially more liberal, were uncomfortable with the socialistic economic policy of Labour and did not cross over to vote. This goes to the heart of one of the reasons the Left is faltering worldwide: its traditional base now values culture more than the economy; the conservative base still values the economy more than culture.

Understanding the above phenomenon and the Achilles heel that afflicts the conservative nationalists to form global alliances can help fuel a resurgence of the economic left around the world. In the name of nationalism, under the guise of social warriors fighting for erstwhile leftist voters, various parties have instead surreptitiously become foot-soldiers for rewarding the economic promises to the conservative base. Considering that liberal values can be more international, if the leftist parties engage more with each other internationally to promote and protect the economy and culture of their bases, they will emerge back as ruling parties across the world.

Consider the case study of Mette Frederiksen, the current leader of Social Democrats and Prime Minister of a truly progressive country like Denmark. During her election in 2019, she ran on an unabashedly liberal economic platform. She, however, moved away from an open immigration system to a system that prizes repatriation over the residence, which is going to come into even sharper focus as the global economy shrinks due to the pandemic. Now consider a truly left-wing government in a developing country like ours. Would such a government like to prioritize the migration of our best talents abroad, or would they want our best talents to stay back and help India achieve self-reliance in multiple sectors? Tying up with a liberal government in Denmark would help train and retain our best talents in India. Simultaneously, foreign investment by Denmark can also be negotiated as the trained quality of personnel in India will now meet Danish standards.

Bringing back our best talents also serves to act as a social fillip for the constituent of that party as they see members from their own community coming back and they have their own dreams of social mobility. The reason the traditional working class has felt a keen need to embrace culture is that they have been left behind in globalization and they have seen a lot of change without progress. When one sees progress personally, it is easier to accept change; when progress stalls, the status quo naturally appeals. The moment they again find a ladder to climb and they find people from their own community coming back as successful professionals; they will dare to hope again. The Left thereby maintaining a semblance of cultural status quo, while providing a live example for economic mobility, would have succeeded in winning back India.

Those of a progressive persuasion should make this their guiding light, in this writer’s contention because leftist alliances are easier to form across the globe. A Narendra Modi government, however close he is personally to Boris Johnson or Donald Trump, will never be able to negotiate either more immigration into the UK or the USA or more aid out of the UK or the USA into India, which contravenes their nationalist ideology. On the contrary, a liberal government in India will be able to tie up easily with another liberal government whose voters do not see Indians or brown-skinned people as threats, but someone to be helped in their own nations. If we help those governments by retaining our talent, we would have formed a natural alliance and done better for our own nation. The campaign cry of the Left in India should not throw people out of communities or bring immigrants from other nations, but rather the promise of the return of the same sons and daughters who moved away and left them behind.

There exists a glorious chance for the Left to win back what it has lost by acknowledging the cultural threats its traditional voting block faces and helping them with local self-reliance, without causing much upheaval amongst the community and with international cooperation. Because if the Left keeps appealing to right-wingers to win them over, the pound of flesh they have to give up will ensure only a skeleton of the original progressive ideology will remain. And that helps no one.

Comments are closed.