With the launch of Sputnik 1 in 1957, Earth’s exploration of space began in earnest. Since then, the focus had been primarily on two countries—Russia and the United States—although, in more recent times, India, China, Japan, and a host of others have made remarkable strides in the exploration of Earth’s orbit, the Moon, Mars and beyond. However, Iceland has played an important role in space exploration since the 1960s and continues to do so. Today the country has its sights set on becoming a member of the European Space Agency (ESA).

Iceland’s unique geography, its technical expertise, and its keen interest in participation on the world stage have all played a part. Its involvement in space exploration has included the launching of a from Langanes just last August; the ongoing development of AI and remote sensing technologies; the study of Iceland’s pristine lava caves as a means to ascertain the possibility of building habitats on Mars, where such caves could shield new inhabitants from the unforgiving levels of radiation that bombard the planet; and the development of what may become Iceland’s very first orbital satellite. In this feature, we spoke with a few of the people trying to make Iceland’s role in space exploration even greater.

Walking on the moon

While the Soviet Union and the US engaged in a heated competition to achieve a series of firsts in space exploration, the former had been outpacing the latter for years, and Iceland largely stayed out of it. The 1950s and 1960s had been a time of prosperity for Iceland, but it remained largely neutral during the Cold War, focusing instead on internal matters and enjoying the wealth of -WW2 years.

Space Iceland

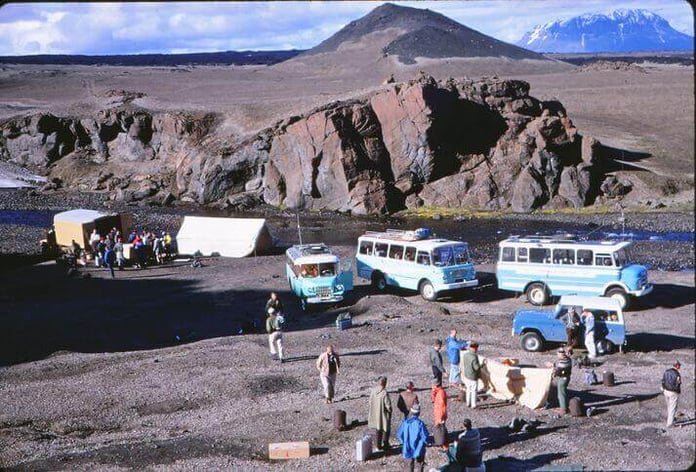

All that changed in 1965, when NASA sent prospective astronauts to Iceland to train for a potential moon landing. They were sent again in 1967. In all, 32 astronauts trained in Iceland and 14 who would eventually get to the moon—including Neil Armstrong—trained here first.

The reason was simple, best summed up by Apollo Program geologist Dr. Elbert A. King: “We took one of our best field trips to Iceland. If you want to go to a place on earth that looks like the Moon, central Iceland should be high on your list, as it beautifully displays volcanic geology with virtually no vegetation cover.”

“When the Americans went to the moon, that was a huge part of space, which was why they came here to train,” Thor Fanndal, the director of Space Iceland, explains. “The reasoning was that obviously, we have an amazing environment when it comes to space. Iceland does look a bit like the moon, and even more like Mars. The astronauts were mostly pilots; they weren’t scientists. There was a need for them to have the ability to pick the best rocks, for example, for analysis down here. NASA at first attempted to teach them in classrooms, and apparently, they showed absolutely no interest in it. So the idea came up that maybe they should do field trips.”

Today, you can visit the Astronaut Monument, located outside the Exploration Museum in Húsavík, commemorating Iceland’s contribution to the space race. But the adventure didn’t end there.

Enter Space Iceland

Space Iceland, as Thor describes it, is a sort of “knowledge hub” that helps make things happen. As a service entity, they work closely with the Icelandic government and bring together institutions, companies, and individuals who want to do anything space-related in Iceland.

“It’s an odd job, but what’s so odd about it is it’s like any other office job,” he says. “It’s very stressful and mundane most days, but then you have these tidbits that make it a bit weird. Like, ‘we need to go and buy gunpowder’ or ‘meet an institution because we want to send up a rocket’ or welcome astronauts because you’re taking them to train. But 90% of the job is just being on the phone, writing reports, and making sure that everything functions. I feel really fortunate to be able to do this job, but I think a lot of people get disappointed. But in the end the projects we do help with value, create jobs, and contribute to space in particular.”

Thor believes it only natural that Iceland gets even more involved in space.

”We get this question of ‘why should Iceland participate in space?,” he says. “We make a point of telling people that we do participate in space; the only question we’re facing now is do we want to do it on our terms? That it leaves as much investment behind as possible, or do we want to stay in the passenger seat? There’s no real question as to how or why we would participate in space; we’ve been doing it for 50 years.”

Is there life on Mars? Ask Iceland

There is apparently greater potential in Iceland’s environment for learning more about space than just the presence of wide expanses of rocks and sand. Oddur Vilhelmsson, a professor of biology at the University of Akureyri who has collaborated with NASA’s astrobiology projects, believes Iceland could hold clues for how to detect life, present, and past, on Mars.

Oddur first met Thor in Húsavík, where he learned about Space Iceland and became “quite enthusiastic” about the endeavour.

“This opens an exciting door in the field of research with international universities and institutions,” he told us. “There’s a lot of demand now that these institutions come to Iceland and do research related to the field of space. It’d be highly desirable to have a regular budget for this, to welcome these people and assist in the research. Personally, I find it a rather fun and exciting subject; it’s not more complicated than that. I find it fascinating to consider where the ‘edge of life’ is, where one can find microorganisms and where one can’t, why, and why not. This to me, is a fundamental scientific and even philosophical question, which is very exciting. It’s something I’ve been having conversations about with many of my colleagues abroad.”

So how exactly can Iceland’s environment play a part in finding life on other planets such as Mars? Apparently, the answer is in our lava caves.

“We’re working on researching how microorganisms live in these caves here in Iceland, examinewhat chemical processes to look for and wonder how that could apply to the conditions on Mars.”

“On the one hand, [we’re working] in the desert sands of the Highlands and on the other hand, in lava caves,” Oddur says. “Astrobiology is connected to this, as the environment in Iceland, especially in the Highlands, is well suited in many ways as an analog for a planet, especially Mars. The caves are also quite exciting in this context because one of the things that prevent Mars from being friends for life is radiation because Mars has no magnetic field. So if there had at one point been life on Mars, as many belief was the case billions of years ago, the best chance of finding signs of it would be underground. So we’re working on researching how microorganisms live in these caves here in Iceland, examine what chemical processes to look for, and wonder how that could apply to the conditions on Mars.”

That certainly is intriguing, but the question of implementation falls upon one primary factor: money .

“As with so many other things in life, this research depends a great deal on access to funding; to be able to hire scientists and buy the equipment necessary,” Oddur says. “Being a part of the ESA would increase our access to such funding, especially from Europe.”

Iceland’s first satellite?

Closer to home, Thor points out that “only 10% of [the space sector] is actually exploring space. Most of it is understanding the Earth, and furthering our knowledge of humankind.” In fact, he says, we rely on space every day.

“Tinder is space technology,” he says. “It uses GPS and satellite clusters to locate you and find you a partner. I sincerely doubt that these couples are thinking ‘Thank God for the space sector, or we would have never found each other.’”

While Iceland does not, as yet, have a satellite of its own, Jinkai Zhang, a researcher for Space Iceland, is hoping to change that. He is currently designing a prototype for Iceland’s first satellite.

”It’s not for just one purpose; this satellite could be used in multiple ways, providing different services at different times,” he says. “It could be commercial communication or scientific research, conducted by organizations or universities. But what we need to figure out right now is who will provide the biggest sponsorship and who will be a client for such a project. But for what I’ve seen in Iceland, this satellite could be used for the global navigation system, which could be a part of the Galileo navigation system, or it can be used for remote sensing of volcanic activity. This could be really helpful for Icelandic scientific research, in terms of having a faster response to an impending eruption, and build a database for future research.”

Space junk

The subject of building more satellites has been the cause for concern, amongst astronomers in particular. Astronomer James Blake of the University of Warwick recently pointed out that “orbital debris posing a threat to operational satellites is not being monitored closely enough, as they publish a new survey finding that over 75% of the orbital debris they detected could not be matched to known objects in public satellite catalogs.”

“orbital debris posing a threat to operational satellites is not being monitored closely enough, as they publish a new survey finding that over 75% of the orbital debris they detected could not be matched to known objects in public satellite catalogs.”

Thor is less concerned about the number of satellites in orbit around Earth, saying, “When it comes to people who talk about ‘space junk’, we should have in mind that there are thousands of ships in the ocean right now, and they very rarely see each other. So multiply that space by hundreds of thousands. The amount of space up there is enormous. Space debris is an issue, but it’s not because we’re running out of space.”

Blue Planet, green energy

For his part, Jinkai sees a great deal of potential in an Icelandic satellite program and says interest is growing.

“Currently, I’m just working in the office, doing research and writing reports, so I don’t have direct contact with the Icelandic government,” he says. “But from what I’ve been doing, I think Iceland has a lot of potential interest in this subject because Icelanders have relatively good telecommunications. The interest in the space program has been increasing in recent years, too. From what I’ve seen, it’s quite possible for Iceland to have such a satellite project; I’m quite positive about this.”

That interest is not just confined to satellites alone.

“Iceland has a really good background in the space industry through history,” Jinkai says, adding that Iceland is also a good model for how a colony on the moon or Mars could thrive. “Iceland has very similar environments [to these places], and really good energy policy in terms of renewable energy. And that’s what we need for developing humanity in outer space.”

Even Iceland’s geothermal and hydropower energy have a role to play in space exploration, he believes.

“There’s a lot of possibilities,” he says. “Iceland has been growing in the field of software engineering, so it could be a control base for the future of space exploration, for example by developing software for the rocket navigational system, or designing simulations for the challenges we’ll face in space exploration. At the same time, we can use Iceland as testing and construction for future spacecraft, because we have a very positive renewable energy policy.”

“There’s a lot of planning, there’s a lot of international contracts involved and so there’s this need for the government to be involved on a policy level.”

Government “aggressively absent”

Thor characterizes the Icelandic government’s participation in space as “aggressively absent”, pointing out that there are some things that only the government can do.

“The government is in no way in our way; they’re not working against us or something like that,” he emphasizes. “But the problem with developing a space sector is that it is a bit different than opening a gift shop. There’s a lot of planning, there’s a lot of international contracts involved and so there’s this need for the government to be involved on a policy level.”

Part of the reason for the current situation can be attributed to the fact that Iceland has no Ministry of Space. It doesn’t have an Icelandic Space Agency, either. All the different factors that play into how Iceland participates in space fall under many different ministries.

“What we’re trying to convince the government of is that we need a ministry that is willing to sign the papers and coordinate with other ministries,” Thor says. Their projects could fall under the ministries of the Environment, Innovation, Education & Science, Transportation, and sometimes Foreign Affairs. “We need all of them to be aware and review what happens under their auspices.”

That said, Space Iceland has reportedly had very positive contact with the Ministry of Education & Science. “I think it’s fair to say that the minister who has shown the most interest and who has been the most welcoming is Lilja [Alfredsdottir, the Minister of Education and Science],” Thor says. “It’s important to note that we’ve had very positive communication with all of them, but I think the Ministry of Education and Science has put the most time into reviewing this and trying to make it fit.”

Space is “a world without borders”

We reached out to Lilja for comment on this matter and she confirmed her interest in space is many-fold.

“Space research and science is appealing for many reasons, both educational and practical,” she told us. “It helps us grapple with the fundamental questions about our place in the universe, the history of the solar system, and future opportunities. Space is a world without borders, it encourages international cooperation and, hopefully, peace in the long term. The practical applications of space have made our lives easier, created job opportunities, and orbital satellites have certainly been used in one of the biggest challenges faced by our planet: the effects of climate change.”

While Lilja admits that establishing an Icelandic Space Agency “has not been discussed” within the government, she points out that Iceland joining the ESA “has been encouraged by Parliament,” although Iceland’s entry has yet to become a reality.

“Iceland will obviously not play a huge role in the field of space science, but we could offer assistance or expertise that can be used in a greater context,” she says. “At the same time, we must be careful, as space research and science are foreign to the government and to the general public. But they are exciting and we should not close our doors in this area.”

Thor agrees and believes Iceland must act quickly. Whether in geology, biology, software engineering, or even the crafting of our first satellite, the time for Iceland’s participation in space is now. Talks with the ESA are reportedly further along at the time of this writing, and preparations for a space launch are underway.

“The opportunity is now and the window will soon close,” he says. “We’re going to Mars within the next couple of decades.” While Icelanders will never be indispensable, he says, “what we can do is be amazingly focused and organized and get as much long term value for anything as possible.