The 90th anniversary of the birth of Oleg Popov, the “sunny clown”, as he was called all over the world for his straw hair and the invariable kind smile that crowned each reprise. The television broadcast a small portion of nostalgic programs, the circus was completely silent due to quarantine … But really, what happened to clown art? Why earlier, if you ask a random passer-by what kind of laughing arena he knows, you would be immediately named a bunch of names – Karandash, Nikulin and Shuydin, Yengibarov, the same Popov – then today your counterpart will most likely frown his brow and … will not remember anyone?

A smile and a cap – it was impossible to imagine Popov in the arena without them (“Soviet Circus”, 1957, No. 2)The history of modern clown art began with the brothers Vladimir and Anatoly Durov. They were the first to abandon the centuries-old make-up of booth jesters and went out to the viewer with an open face. From the past image, only a drawn curved eyebrow remained, a kind of sign of professional belonging, in all other respects the artists appeared before the public as their own unique personality.

It was this tradition that was adopted by the Soviet circus, where the clown, as the embodiment of theatrical, dramatic, semantic principle, became the central figure of the performance.

In the forties in Moscow, clowns were trained at the Studio of Conversational Artists. It was there that Yuri Nikulin went after he failed at VGIK and GITIS. There he came under the mentorship of the famous Karandash (Mikhail Rumyantsev), met his future partner Mikhail Shuydin – and the most famous clown tandem of the Soviet Union appeared.

The school of clowns subsequently changed its name (becoming the Studio of Clownery), its head (in 1964, it was headed by the famous director of the Moscow Circus on Tsvetnoy Mark Mestechkin), but, having existed until the 1980s, it invariably retained its focus on educating and actor-personality.

How different they are! Someone focused on mastering all circus genres, like Pencil, Oleg Popov, Andrei Nikolaev, Vladimir Kremena, or a couple of Gennady Rotman – Gennady Makovsky. There were phrasebook clowns who built their repertoire on dramatic scenes: the same Nikulin and Shuydin, Valentin Kosterenko – Lev Zinoviev, the Sherman brothers. Later, a pantomime appeared on the arena, the wizard of gesture Leonid Yengibarov shone in it …

What is the secret of this variety of manners? Of course, without natural talent, there is no point in talking about any art. But talents are born everywhere, but not everywhere the stars gather in constellations. Here we have to say something unfashionable today: the attention of the state played a huge role in the formation of the Soviet clown school.

The Artistic Council of the Union State Circus strictly monitored that each individual artist or clown couple did not resemble each other, and that reprises and images were not repeated. The basis of the council was, of course, professionals, but so that the eyes did not get blurry, the audience was also invited there. Here, for example, what the magazine “Soviet Stage and Circus” wrote in 1980: “Members of the Arts Council are entrusted with keynote speeches at meetings devoted to discussing performances. At one such discussion, the turner of the construction machinery plant, Hero of Socialist Labor E. Moryakov made a presentation. His analysis of the numbers (and, I must say, very professional) was listened to by the artists with great interest, provoked a lively debate. ” Are you smiling at naive populism? And then the audience did not smile – they were tearing their bellies with laughter at circus performances.

No, it was not at all on the “party will” for 12 years that Boris Vyatkin’s performances were on er of the Leningrad circus. “Nikulin and Shuydin,” recalls the wife and stage partner of Yuri Vladimirovich Tatyana Nikolaevna Nikulina, “had 60 reprises! And today’s clowns have six or eight at best. ”

“While Western clownery did not bother with delights, but worked with stereotyped characters – some faceless pair” White – Red “or” Fat – Thin “, the Soviet school was famous for its dramaturgy, – says a senior teacher at the circus directing department of GITIS. Lunacharsky, former trapeze artist Irina Talina. – Each clown reprise was a small finished work. A whole galaxy of authors, including very famous ones, specialized in this genre: Leonid Kukso, Yakov Kostyukovsky, Mark Trivas, Fedor Lipskerov, Zinoviy Yuriev … “.

This, perhaps, will especially surprise today’s reader – one of the main advantages of Soviet clowns was the art of improvisation, which seemed to not fit into a rigid ideological system. Pencil, Nikulin, and Shuydin, Konstantin Musin mastered it perfectly. The latter could go to the arena without any props at all, cling to any detail, even the broom of a uniformists, and give a full-fledged reprise according to all the laws of drama – with the beginning, development, and end.

Sometimes, in such free fantasies, the artists allowed themselves sensitive critical injections. For example, Viktor Kovalenko was once burnt in the sun, and in the evening he had to go out to the arena. The clown was not taken aback and decided to use this in an instantly composed reprise. He appeared in the arena, deliberately wincing in pain, and to the question of the arena inspector: “Where, Vitya, are you so burned?” answered: “In line for meat!” The hall exploded with laughter – however, the artist was then deprived of performances for six months and transferred to the uniform.

But the story did not end there. In one of the programs, Yuri Nikulin, who seemed to be “scorched” in the sun, entered the arena. “Yurik, where did you get so burned?” – “In the queue,” Nikulin began to answer, then took a long pause, from which Anatoly Kolevatov, the director of the Soyuz State Circus, who was sitting in the box, caught his breath, and suddenly exclaimed: “… For Ogonyok!” … Kolevatov felt relief from his heart – they could not punish for promoting his native Soviet press.

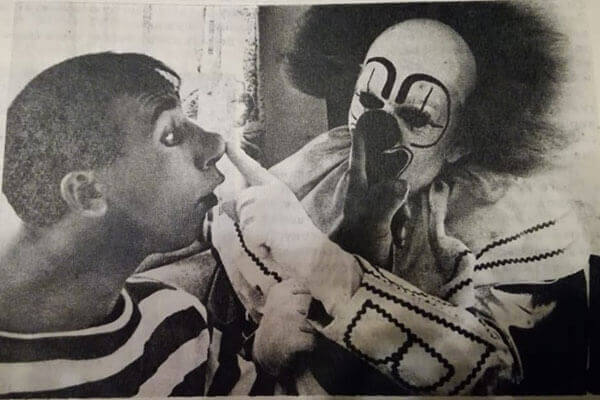

Pencil before going on stage (“Soviet Circus”, 1958, No. 4)Well, about Oleg Popov. One of the symbols of the national circus, Oleg Konstantinovich, oddly enough, was not so stunningly funny. And he usually didn’t risk improvising – all his recitals were verified with mathematical precision, up to the number of steps from one point of the arena to another. His strength was in the virtuoso possession of many circus genres: balancing act, juggling, acrobatics, especially balancing on a free wire. A virtuoso cascade of tricks plus the image of a Russian guy with straw hair in a checkered cap created by a whole team of artists, makeup artists, and stylists made the artist his own on the board for our audience and an attractive exotic person for foreign ones. It is no accident that it was Popov who was most often sent on foreign tours, from where he brought a fair amount of hard currency to his homeland. In 1971 in Melbourne at the annual Mumba arts festival, he was elected king of the holiday. Among Australians, accustomed to seeing their jesters under a thick faceless make-up, the image of a “clown with a human face” caused a furor.

But the funny thing, or rather sad, is that today the situation has turned upside down – Western clowns have successfully adopted our experience and are increasingly performing with interesting reprises in a variety of genres. As, for example, a native of Russia, but long ago became a foreigner Khush-Ma-Khush (Semyon Shuster), the American wagon clown Bello Nock, the Portuguese Cesar Diaz, the Austrian Don Christian, the Italian David Larible (by the way, several seasons with success in Moscow) …

And our artists, on the contrary, brought from the West several supposedly win-win clown chips – for example, pulling random spectators out of the hall, who are forced to do obviously unbearable tricks, making them look like fools. And this primitive technique wanders from program to program.

Probably, one could name many reasons for the crisis of the genre, but the main one is banal: state funding has fallen sharply, and there are no patronage traditions.

To be fair, let’s say that the leaders of the Rosgoscirk sometimes try to change something – for example, Vadim Gagloyev, being at the head of the company, established the international award of circus art “Master”, and within its framework, Oleg Popov even managed to award the honorary award “Legend of the Circus “. However, the idea with the prize lasted only two years and died out with the departure of Gagloyev from . Successor Dmitry Ivanov tried to organize a clown school under the direction of director Andrei Sharnin. They invited good masters, drew up a program – but for some reason, there was no staff inflow.

“Talents have not died out,” says Irina Asaturyan, head of the production and creative department of the Russian State Circus. – The eccentric Sergei Prosvirnin holds the bar, in recent years performing with his son Sergei Jr., and now his grandson is also working with them. Dynasty is a great sign of genre vitality! There is also a couple, Stanislav Knyazkov and Vasily Trifonov, a very promising recent graduate Ignat Starichikhin. They also praise the young clown Vladislav Bogdanov … ”.

Let’s add to this list Vladimir Deryabkin, Boris Oskotsky, a couple of “Grandsons of Lieutenant Schmidt” (Sergei Kolganov – Oleg Belogorlov) … But how many people know about them? Previously, the circus artist was a welcome and obligatory participant in the television “Lights”, but on the current television real circus people are shy, preferring to them amateur exercises of pop stars. Is it clowning here?