Of course, madrasah education is an important educational sector in Bangladesh. It provides Islamic education and contributes to society in terms of religious affairs. Indeed, many madrasah-educated individuals are engaged with diverse sorts of religious activities including carrying out religious functions such as prayers and religious rituals in the society. At present, there are thousands of madrasahs and millions of madrasah students in the country. But, of course, madrasah education has a wide range of problems. As a consequence, madrasah education fails to play its roles as desired. In this article, I will comment on some major aspects of madrasah education.

Of course, the madrasah education system evolved gradually and come to the present stage in Bangladesh. Historically, madrasah education began in Saudi Arabia by the last prophet Hazrat Muhammad (Sm) and, later, it spread to different Arab countries and other regions. As it appears, the mosque-based Madrasah education was initially introduced in the Indian subcontinent in the 8th century, but it was introduced in the Bengal after the conquering of the Bengal by Ikhtiar Uddin Muhammad Bin Bakhtiar Khaljee in 1204 and during the Sultani era (1210-1576). Of course, the scope of madrasah education expanded during the Mughal era with the inclusion of different branches of knowledge including religious, philosophical and scientific. Afterward, madrasah education was further diversified in Bengal with the establishment of the Aliya madrasah system (Kolkata Aliya Madrasah) in 1780 and the Quwmi Madrasah system (the Darul Ulum Deoband Madrasah) in 1866. Quwmi Madrasahs subsequently originated and flourished in Bangladesh with the establishment of Chittagong Darul Ulum Moyeenul Islam Madrasah in 1899 in conformity with the Deoband Madrasahs in India.

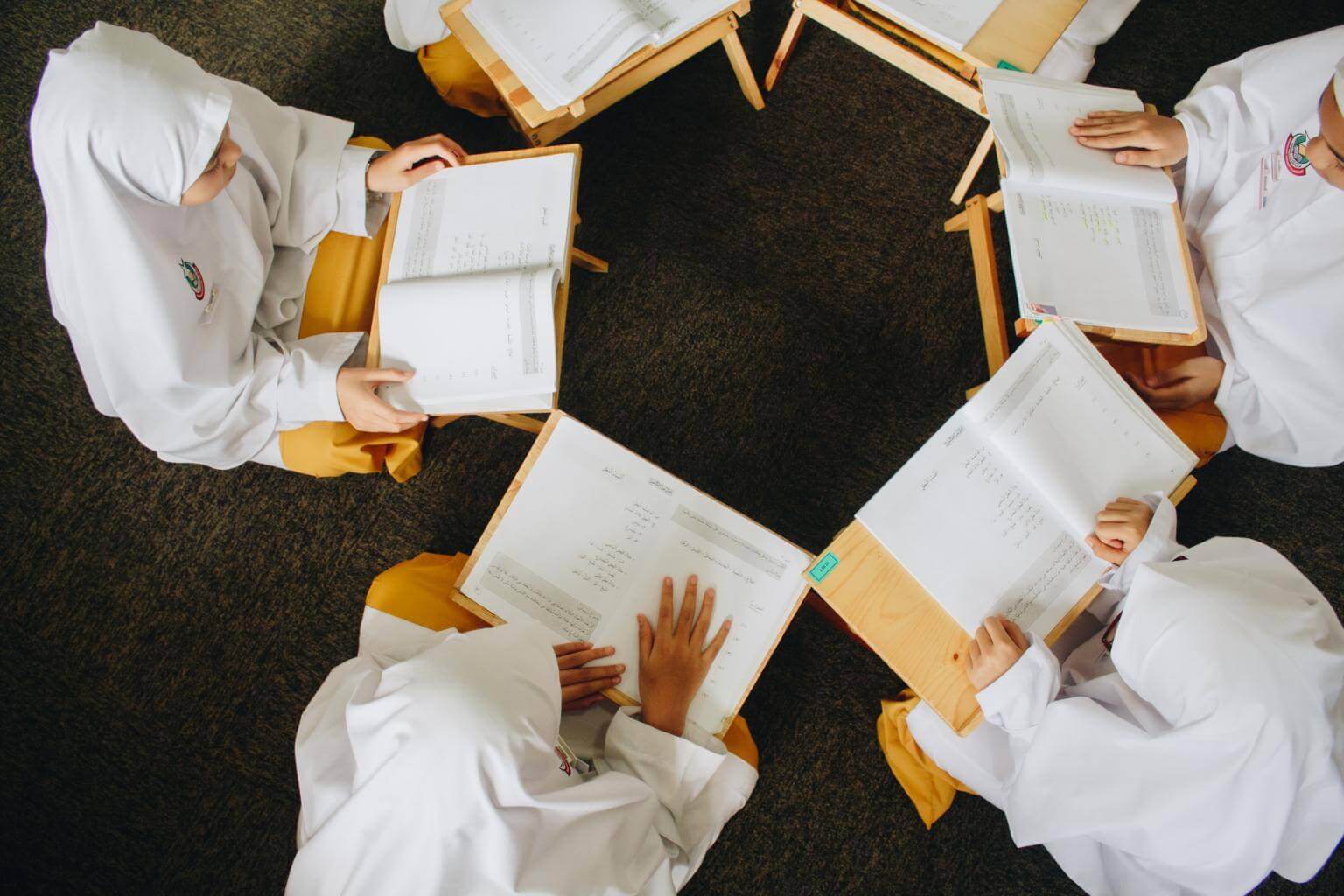

In Bangladesh, there are currently several types of madrasahs such as Alia, Qawmi and others including Maktab, Hafizul Quran and cadet madrasahs. In Alia Madrasah, both general and religious education is given at Ebtadayee (primary), Dakhil (secondary), Alim (higher secondary), Fazil (undergraduate) and Kamil (post-graduate or masters) levels. In Qawmi madrasah, education of Qawmi madrasah at Tahfeezul Quran (Memorization of the Qur’an), Ibtedayi (primary), Mutawassitah (lower secondary), Sanariaammah (secondary), Fazilat (Bachelor degree) and Takhmil (post-graduate or Masters) levels. Qawmi education system practices the traditional Muslim education system of Bangladesh. In traditional Maktab, the Quran and Arabic are taught to the children. In the Hafizul Quran madrasah education system, the Quran is memorized by students. In Cadet madrasah, some sort of Islamic education is given to students.

Of the different types of madrasahs, only Alia madrasahs are regulated by the government but others are not. Alia madrasahs follow government curriculum at primary, secondary and higher secondary level and but curriculums of other levels — undergraduate and post-graduate — are made through combining general education and Islamic education. Primary, secondary and higher secondary educations in Alia madrasah are regulated by the Bangladesh Madrasa Education Board, but Fazil and Kamil are regulated by Islamic University as per the Islamic University Amendment Act of 2006. But Qawmi madrasahs are financed by private donors and are run independently. Several boards with a common name — Bangladesh Qawmi Madrasah Education Boards or Befaqul Madarisil Arabia Bangladesh — regulate affiliated Qawmi madrasahs following the syllabus of Darul Uloom Deoband. But other Qawmi madrasahs are private and run by local people and follow courses designed by respective institutes.

As noted already, there are various limitations to madrasah education. Diverse problems can be explained by content, resources, management and administrative and outcome-based problems. Content-related problems are major causes for concerns. Some content-related problems are mostly focusing on religious values, outdated syllabus and stereotyped curriculum, less emphasis on science education, less emphasis on social values, inadequate emphasis on technical education, etc. Due to inadequate emphasis on science, most madrasah students become ineligible for scientific thinking and are more likely to develop a negative attitude towards science in general, even if science is not against any religion by its nature. Moreover, disregarding social values not leads to the alienation of madrasah students from society but also makes madrasah students and madrasah educated individuals unreasonably harmful to society on some occasions.

Resource-related problems put significant barriers to effective and desired madrasah education. Some resource-related concerns are lack of quality educational institutions, a shortage of quality teachers, a shortage of teacher training facilities, etc. Although all sorts of madrasahs suffer from diverse resource-related problems, there are variations in this regard. In fact, Qawmi madrasah has more resource-related problems. Because of a lack of quality teaching staff-related problems, proper education to madrasah students becomes difficult. Indeed, a lack of qualified, or broadly knowledgeable, teachers in madrasas and a lack of quality educational facilities are the main reason behind madrasah students’ poor basic knowledge of science and varied socio-econoimc and cultural aspects that are important for human beings and society. On some occasions, madrasah students are unacceptably misguided — knowingly and unknowingly.

Management and administrative limitations put a considerable hindrance to madrasah education in Bangladesh. Some notable management-related problems are lack of adequate management of madrasah education, lack of effective madrasah committee and staffing and salary scale and lack of supervision on putting extensive pressure on students. It is undeniable that most madrasahs of Bangladesh are managed privately, even if Aliya madrasahs are regulated by an established and recognized governing body. Although there are some sorts of organized management of Qawmi madrasahs too, these are inadequate. Poor management creates other problems including financial management, the recruitment of quality teachers and inappropriate guidance to students.

Outcome-related problems of madrasah education are to be specially mentioned here. Some outcome-based concerns are producing inadequate Islamic scholars, Islamic thinkers with a narrow focus on religion, low-skilled manpower and a negative attitude among madrasah-educated individuals towards general education. Though students of Aliya madrasahs have opportunities to the job market, students passed from Aliya madrasahs and other madrasahs (mentioned above) are lagging far behind. As expected, around 75 percent of madrasa students remain unemployed in different forms due to a lack of job-focused and skills-based education. Although there are some genuine Islamic thinkers, many Islamic thinkers passed from madrasahs narrowly explain religious affairs.

As expected, all the above-noted limitations to madrasah education need to be well-addressed with some effective measures. In this respect, the modernization of all madrasah education systems is to be given special emphasis. It is undeniable that for the modernization of madrasah education, some steps were taken in the past and are being considered at present. Such an intention is reflected in the Madrasah Education Ordinance of 1978 and the recent recognition of dawra-e-hadith as equivalent to a post-graduate degree. But something more needs to be done for reasonable modernization of madrasah education. In the modernization efforts, special emphasis should be given on the introduction of up-to-date or quality education and science, skills and social values-based curriculum, along with the presence of core religious texts.

In addition, some other measures including providing adequate training to madrasah teachers, securing transparency in management, providing resource-related supports, addressing negative attitudes towards women’s education and securing some sort of regulation of Qawmi and other madrasahs are important for improving the overall madrasah education system in Bangladesh. I think that a well-thought reform of madrasah education and addressing all reasonable causes of concerns can make madrasah education more meaningful, help produce religious thinkers capable of viewing diverse problems broadly and increase its contributions as desired. But, of course, reformation should not undermine religious education in a genuine sense at all.

Comments are closed.